Parallel Computing

Concurrency is when two or more tasks can start, run, and complete in overlapping time periods. Parallelism is when tasks literally run at the same time, eg. on a multi-core processor.

Parallel computation has become increasingly common. Laptops and desktops come with multiple processors which communicate through shared memory (shared memory model). High-end computation is often done using clusters consisting of individual computers communicating through a network (distributed memory model).

Parallelism provides a number of benefits: high performance, better use of resources, fairness, convenience, fault tolerance.

Writing correct parallel programs is challenging because of the subtle interactions between parallel components.

- race (two concurrent instruction sequences access the same address in memory and at least one of them writes to that address.)

- starvation (a processor needs a resource but never get it.)

- deadlock (thread A acquires lock L1 and thread B acquires lock L2, following which A tries to acquire L2 and B tries to acquire L1.)

- livelock (a processor keeps retrying an operation that always fails).

Bugs caused by these issues are difficult to find using testing, also difficult to debug because they may not be reproducible since they are usually load dependent. The overhead of communicating intermediate results between processors can exceed the performance benefits.

Try to work at a higher level of abstraction. In particular, know the concurrency libraries, don’t implement your own semaphores, thread pools, deferred execution, etc. (You should know how these features are implemented, and implement them if asked to.)

If you writing a mutable class, you have two options: allow the client to synchronize externally if concurrent use is required; or make the class thread-safe (synchronize internally). HashMap vs. ConcurrentHashMap.

If a method modifies a static field and there is any possibility that the method will be called from multiple threads, you must synchronize access to the field internally. Because this field is essentially a global variable even if it is private because it can be read and modified by unrelated clients.

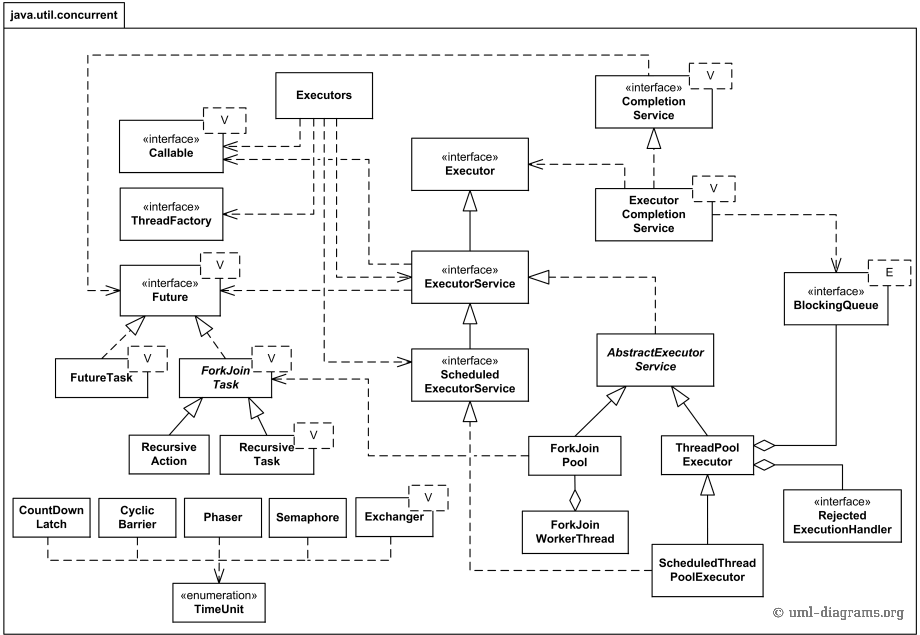

Since Java 5, the platform has provided higher-level concurrency utilities that do the sorts of things you formerly had to had-code atop wait and notify. The utilities fall into three categories: Executor Framework; Concurrent Collections (especially BlockingQueue); Synchronizers (Semaphore, CountDownLatch, CyclicBarrier and Exchanger).

For interval timing, always use System.nanoTime rather than System.currentTimeMillis as System.nanoTime is both more accurate and more precise and is unaffected by adjustments to the system’s real-time click.

ConcurrentHashMap

A hash table supporting full concurrency of retrievals and high expected concurrency for updates. However, even though all operations are thread-safe, retrieval operations do not entail locking, there is not any support for locking the entire table in a way that prevents all access. This class is fully interoperable with Hashtable in programs that rely on its thread safety but not on its synchronization details.

Retrieval operations (including get) generally do not block, so may overlap with update operations (including put and remove). Retrievals reflect the results of the most recently completed update operations holding upon their onset. They do not throw ConcurrentModificationException.

A ConcurrentHashMap has internal final class called Segment so we can say that ConcurrentHashMap is internally divided in segments of size 32, so at max 32 threads can work at a time. It means each thread can work on a each segment during high concurrency and at most 32 threads can operate at max which simply maintains 32 locks to guard each bucket of the ConcurrentHashMap. This is also called lock stripping and StripedLock is provided in Google Guava.

public final Segment[] segments = new Segment[32];

public V put(K key, V value) {

int hash = key.hashCode();

Segment segment = segments[hash & 0x1F]; // 0~31

synchronized (segment) {

int index = hash & table.length - 1;

Entry<K, V> first = table[index];

for (Entry<K, V> e = first; e != null; e = e.next) {

if (e.hashCode() == hash && key.equals(e.getKey())) {

V oldValue = e.getValue();

e.setValue(value);

return oldValue;

}

}

table[index] = new Entry(hash, key, value, first);

}

return null;

}

Java Memory Model

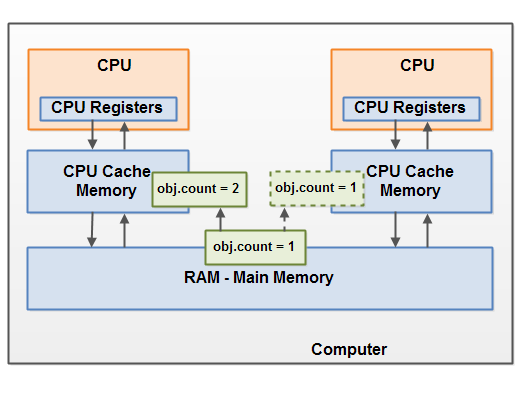

The following diagram illustrates the sketched situation. One thread running on the left CPU copies the shared object into its CPU cache, and changes its count variable to 2. This change is not visible to other threads running on the right CPU, because the update to count has not been flushed back to main memory yet.

To solve this problem you can use Java’s volatile keyword. The volatile keyword can make sure that a given variable is read directly from main memory, and always written back to main memory when updated.

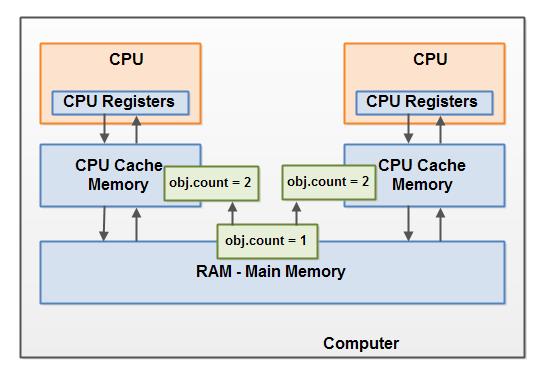

This diagram illustrates an occurrence of the problem with race conditions as described above:

To solve this problem you can use a Java synchronized block. A synchronized block guarantees that only one thread can enter a given critical section of the code at any given time. Synchronized blocks also guarantee that all variables accessed inside the synchronized block will be read in from main memory, and when the thread exits the synchronized block, all updated variables will be flushed back to main memory again, regardless of whether the variable is declared volatile or not.

Shared Variable

Do not use Thread.stop. A recommended way is to use a boolean flag with the volatile modifier, it guarantees that any thread that reads the field will see the most recently written value.

public class StopThread {

// You can also use AtomicBoolean directly!

private static final volatile boolean stopRequested;

// Lock-free, thread-safe primitives within java.util.concurrent.atomic

private static final AtomicLong nextSerialNum = new AtomicLong();

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

Thread backgroundThread = new Thread(() -> {

int i = 0;

while (!stopRequested) {

System.out.println(i + ": " + nextSerialNum.getAndIncrement());

i++;

}

});

backgroundThread.start();

Thread.sleep(10);

stopRequested = true;

}

}

Lazy Initialization

Under most circumstances, normal initialization is preferable to lazy initialization.

If you need to use lazy initialization for performance on a static field, use the lazy initialization holder class idiom.

public class LazyInitialization {

// Lazy initialization holder class idiom for static fields

private static class FieldHolder {

static final FieldType field = computeFieldValue();

}

private static FieldType getField() {

return FieldHolder.field;

}

// Double-check idiom for lazy initialization of instance fields

private volatile FieldType field;

private FieldType getField2() {

// local variable result is to ensure that field is read only once

// in the common case where it's already initialized. (but it's optional)

FieldType result = field;

if (result == null) { // First check (no locking)

synchronized (this) {

if (field == null) // Second check (with locking)

field = result = computeFieldValue();

}

}

return result;

}

}

A Semaphore Sample

A semaphore is a very powerful synchronization construct, which maintains a set of permits. Semaphores are often used to restrict the number of threads that can access some resource.

Synchronization is not guaranteed to work unless both read and write operations are synchronized.

public class Semaphore {

private final int maxAvailable;

private int taken;

public Semaphore(int maxAvailable) {

this.maxAvailable = maxAvailable;

this.taken = 0;

}

public synchronized void acquire() throws InterruptedException {

while (taken == maxAvailable) {

wait();

}

taken++;

}

public synchronized void release() throws InterruptedException {

taken--;

// notifyAll in place of notify protects against accidental or malicious waits by an unrelated thread. Such waits could otherwise "swallow" a critical notification, leaving its intended recipient waiting indefinitely.

notifyAll();

}

}

Synchronized Keyword

You can have both static and non-static synchronized method, and synchronized blocks in Java. You can NOT have synchronized variable, but you can have volatile variable as shown above, which will instruct JVM threads to read the value of the volatile variable from main memory and don’t cache it locally. Block synchronization in Java is preferred over method synchronization in Java because by using block synchronization, you only need to lock the critical section of code instead of the whole method. Since synchronization in Java comes with the cost of performance, we need to synchronize only part of the code which absolutely needs to be synchronized.

public class SlingshotCache implements EventListenerInterface {

private static SlingshotCache instance = null;

public static SlingshotCache getInstance() {

if (instance == null) {

// synchronize on class level due to instance is static variable!

synchronized (SlingshotCache.class) {

if (instance == null) {

instance = new SlingshotCache();

}

}

}

return instance;

}

public int saveMonitorAlerts(Date cutoffTime) {

ArrayNode alertsArray = null; // lazy initialization!

int alertsCount = 0;

// synchronized on variable level

synchronized (monitorAlerts) {

for (MonitorAlert alert : monitorAlerts) {

if (alert.getTimestamp().before(cutoffTime)) {

// just send over top 100 alerts

if (alertsCount < 100) {

if (alertsArray == null)

alertsArray = jsonMapper.createArrayNode();

ObjectNode entryNode = jsonMapper.createObjectNode();

entryNode.put("timestamp", Constants.timestampFormat.format(alert.getTimestamp()));

entryNode.put("channel", alert.getChannel().name());

entryNode.put("severity", alert.getSeverity().name());

alertsArray.add(entryNode);

}

alertsCount++;

}

}

}

}

}

Analyze Two Interleaved Threads

The following code shows: Threads t1 and t2 each increment an integer variable N times. What are the max and min values that could be printed by the program as a function of N?

public class TwoThreadIncrement {

public static class IncrementThread implements Runnable {

public void run() {

for (int i = 0; i < TwoThreadIncrementDriver.N; i++) {

TwoThreadIncrementDriver.counter++;

}

}

}

public static class TwoThreadIncrementDriver {

public static int counter; // unguarded by volatile modifier or synchronized method

public static int N;

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

N = (args.length > 0) ? new Integer(args[0]) : 100;

Thread t1 = new Thread(new IncrementThread());

Thread t2 = new Thread(new IncrementThread());

t1.start();

t2.start();

t1.join();

t2.join();

System.out.println(counter);

}

}

}

Solution: Please note that the increment code is unguarded, which opens up the possibility of its value being determined by the order in which threads that write to it are scheduled by the thread scheduler.

The maximum value is 2N. This occurs when the thread scheduler runs on thread to completion followed by the other threads.

When N = 1, the minimum value for the count variable is 1: t1 reads, t2 reads, t1 increments and write, then t2 increments and writes.

When N > 1, the final value of the count variable must be at least 2 because . There are two possibilities. A thread, call it T, performs a read-increment-write-read-increment-write without the other thread writing between reads, in which case the written value is at least 2. If the other thread now writes a 1, it has not yet completed, so it will increment at least once more.

The lower bound of 2 is achieved according to the following thread schedule:

- t1 loads the value of the counter, which is 0.

- t2 executes the loop N - 1 times.

- t1 doesn’t know that the value of the counter changed and writes 1 to it.

- t2 loads the value of the counter, which is 1.

- t1 executes the loop for the remaining N - 1 iterations.

- t2 doesn’t know that the value of the counter has changed, and writes 2 to the counter.

Synchronize Two Interleaving Threads

Thread t1 prints odd numbers from 1 to 100; Thread t2 prints even numbers from 1 to 100. Write code and make the two threads print the numbers from 1 to 100 in order.

Hint: The two threads need to notify each other when they are done. OddEvenMonitor is built as a Semaphore.

public class OddEvenSynchronization {

public static class OddEvenMonitor {

public static final boolean ODD_TURN = true;

public static final boolean EVEN_TURN = false;

private boolean turn = ODD_TURN;

// Need synchronized in order to call wait()

public synchronized void waitTurn(boolean myTurn) {

while (turn != myTurn) {

try {

wait();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.out.println("InterruptedException in wait(): " + e);

}

}

}

// Need synchronized in order to call notify()

public synchronized void toggleTurn() {

turn ^= true;

notify();

}

}

public static class OddThread extends Thread {

private final OddEvenMonitor monitor;

public OddThread(OddEvenMonitor monitor) {

this.monitor = monitor;

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (int i = 1; i <= 100; i += 2) {

monitor.waitTurn(OddEvenMonitor.ODD_TURN);

System.out.println("i = " + i);

monitor.toggleTurn();

}

}

}

public static class EvenThread extends Thread {

private final OddEvenMonitor monitor;

public EvenThread(OddEvenMonitor monitor) {

this.monitor = monitor;

}

@Override

public void run() {

for (int i = 2; i <= 100; i += 2) {

monitor.waitTurn(OddEvenMonitor.EVEN_TURN);

System.out.println("i = " + i);

monitor.toggleTurn();

}

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

OddEvenMonitor monitor = new OddEvenMonitor();

Thread t1 = new OddThread(monitor);

Thread t2 = new EvenThread(monitor);

t1.start();

t2.start();

t1.join();

t2.join();

}

}

Fix a Concurrency Bug

Identify a concurrency bug in the program below, and modify the code to resolve the issue.

public static class Account {

private int balance;

private int id;

private static int globalId;

Account(int balance) {

this.balance = balance;

this.id = ++globalId;

}

private boolean move(Account to, int amount) {

synchronized (this) {

synchronized (to) {

if (amount > balance) {

return false;

}

to.balance += amount;

this.balance -= amount;

System.out.println("returning true");

return true;

}

}

}

public static void transfer(final Account from, final Account to, final int amount) {

Thread transfer = new Thread(new Runnable() {

public void run() {

from.move(to, amount);

}

});

transfer.start();

}

}

Suppose U1 initiates a transfer to U2, and immediately afterwards, U2 initiates a transfer to U1. The program is possible to get deadlocked. One solution is to have a global lock which is acquired by the transfer method. But the draw back is that blocks transfers that are unrelated.

The canonical way to avoid deadlock is to have a global ordering on locks and acquire them in that order. Since accounts have a unique integer id, the update below is all that is needed to solve the deadlock.

// The id can be used as a global ordering on locks.

// Does not matter if lock1 equals lock2: since

// Java locks are reentrant, we will re-acquire lock2.

public boolean move2(Account to, int amount) {

Account lock1 = (id < to.id) ? this : to;

Account lock2 = (id < to.id) ? to : this;

synchronized (lock1) {

synchronized (lock2) {

if (amount > balance) {

return false;

}

to.balance += amount;

this.balance -= amount;

System.out.println("returning true");

return true;

}

}

}

The Readers-Writers Case

Consider an object s which is read from and written to by many threads. You need to ensure that no thread may access s for reading or writing while another thread is writing to s. (Two or more readers may access s at the same time.)

One way to achieve this is by protecting s with a mutex that ensures that two threads cannot access s at the same time. However, this solution is suboptimal, because no reader is to be kept waiting if s is currently opened for reading.

Here we can use a pair of locks – a read lock and a write lock, and a read counter locked by the read lock.

public class ReaderWriter {

static String data = new Date().toString();

static Random random = new Random();

static Object LR = new Object();

static int readCount = 0;

static Object LW = new Object();

public static class Task {

static Random r = new Random();

static void doSomeThingElse() {

BigInteger b = BigInteger.probablePrime(521, r);

System.out.println(" identified a big prime: " + b.mod(BigInteger.TEN));

try {

Thread.sleep(r.nextInt(1000));

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

// Time to move on.

}

}

}

// LR and LW are static members of type Object in the RW class.

// They serve as read and write locks. The static integer

// field readCount in RW tracks the number of readers.

public static class Reader extends Thread {

String name;

Reader(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public void run() {

while (true) {

synchronized (ReaderWriter.LR) {

ReaderWriter.readCount++;

}

System.out.println("Reader " + name + " is about to read");

System.out.println(ReaderWriter.data);

synchronized (ReaderWriter.LR) {

ReaderWriter.readCount--;

ReaderWriter.LR.notify();

}

Task.doSomeThingElse();

}

}

}

public static class Writer extends Thread {

String name;

Writer(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public void run() {

while (true) {

synchronized (ReaderWriter.LW) {

boolean done = false;

while (!done) {

synchronized (ReaderWriter.LR) {

if (ReaderWriter.readCount == 0) {

System.out.println("Writer " + name + " is about to write");

ReaderWriter.data = new Date().toString();

done = true;

} else {

// Use wait/notify to avoid busy waiting.

try {

// Protect against spurious notify, see

while (ReaderWriter.readCount != 0) {

ReaderWriter.LR.wait();

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.out.println("InterruptedException in Writer wait");

}

}

}

}

}

Task.doSomeThingElse();

}

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread r0 = new Reader("r0");

Thread r1 = new Reader("r1");

Thread w0 = new Writer("w0");

Thread w1 = new Writer("w1");

r0.start();

r1.start();

w0.start();

w1.start();

try {

Thread.sleep(10000);

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.exit(0);

}

}

Add On Write Preference

Based on above solution, the writer W could starve if multiple readers hold the access. How could we protects with “writer-preference”. i.e., no writer, once added to the queue, is to be kept waiting longer than absolutely necessary.

Hint: Force readers to acquire a write lock.

We achieve this by modifying above solution to have a reader start by locking the write lock and then immediately release it. In this way, a write who acquires the write lock is guaranteed to be ahead of the subsequent readers.

Implement a Timer Class

Consider a web-based calendar in which the server hosting the calendar has to perform a task when the next calendar event takes place.

We need a set of functions to manage the calendar and a background dispatch thread to run/delete the tasks. Therefore the two aspects to the design are the data structures and the locking mechanism.

We use two data structures. The first is a min-heap in which we insert key-value pairs: the keys are run times and the values are the thread to run at that time. A dispatch thread runs these threads; it sleeps (wait) from call to call and may be woken up if a thread is added to or deleted from the pool. If woken up, it advances or retards its remaining sleep time based on the top of the min-heap. On waking up, it will loop and peek for the thread (those runTime < currentTime) at the top of the min-heap, then poll and executes it in a thread pool. Meanwhile, use the next top thread’s run time to update the timer’s wake up time.

The second data structure is a hash table with thread ids as keys and entries in the min-heap as values. If we need to cancel a thread. we go to both min-heap and hash table to delete it. Each time a thread is added, we add it to the hash table and min-heap; if the insertion is to the top of the min-heap, we interrupt the dispatch thread so that it can adjust its wake up time.

Since the min-heap is shared by the update methods and the dispatch thread, we need to lock it. The simplest solution is to have a single lock that is used for all read and writes into the min-heap and the hash table. Or just leverage the concurrent package: PriorityBlockingQueue and ConcurrentHashMap.

public class DurationSleeper {

private final Object monitor = new Object();

private long durationMillis = 0;

public DurationSleeper(long duration, TimeUnit timeUnit) {

setDuration(duration, timeUnit);

}

public void sleep() {

long millisSlept = 0; // reset

// Loop checking in favor of setDuration() at any time!

while (true) {

synchronized (monitor) {

try {

long millisToSleep = durationMillis - millisSlept;

if (millisToSleep <= 0)

return;

long sleepStartedInNanos = System.nanoTime();

// Not using System.currentTimeMillis - it depends on OS time,

// and may be changed at any moment (e.g. by daylight saving time)

monitor.wait(millisToSleep);

millisSlept += TimeUnit.NANOSECONDS.toMillis(System.nanoTime() - sleepStartedInNanos);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new RuntimeException("Execution interrupted.", e);

}

}

}

}

public void setDuration(long newDuration, TimeUnit timeUnit) {

synchronized (monitor) {

this.durationMillis = timeUnit.toMillis(newDuration);

monitor.notifyAll();

}

}

}

Java Concurrent Package

-

When you work directly with threads, a Thread serves as both a unit of work and the mechanism for executing it. In the Executor Framework, they are separate: The unit of work is the task (Runnable or Callable); The general mechanism for executing tasks is the executor service.

-

The

Callableinterface is similar toRunnable, in that both are designed for classes whose instances are potentially executed by another thread. ACallablereturns a value and can throw arbitrary exceptions. -

A fork-join task, represented by a ForkJoinTask instance, may be split up into smaller subtasks, and the threads comprising a ForkJoinPool not only process these tasks but “steal” tasks from one another to ensure that all threads remain busy, resulting in higher CPU utilization, higher throughput, and lower latency.

java.util.concurrent.atomic

This package provides primitives for lock-free, thread-safe programming on single variables. While volatile provides only the communication effects of synchronization, this package also provides atomicity.

java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock

-

A ReentrantLock is owned by the thread last successfully locking, but not yet unlocking it. A thread invoking lock will return, successfully acquiring the lock, when the lock is not owned by another thread. The method will return immediately if the current thread already owns the lock.

-

The constructor for this class accepts an optional fairness parameter. When set true, under contention, locks favor granting access to the longest-waiting thread.

-

Condition factors out the Object monitor methods (wait, notify and notifyAll) into distinct objects to give the effect of having multiple wait-sets per object, by combining them with the use of arbitrary Lock implementations. Where a Lock replaces the use of synchronized methods and statements, a Condition replaces the use of the Object monitor methods.

class X {

private final ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

// ...

public void m() {

lock.lock(); // block until condition holds

try {

// ... method body

} finally {

lock.unlock()

}

}

}}

java.util.concurrent.BlockingQueue

BlockingQueue implementations are thread-safe. All queuing methods achieve their effects atomically using internal locks or other forms of concurrency control.

Usage example, based on a typical producer-consumer scenario.

class Producer implements Runnable {

private final BlockingQueue queue;

Producer(BlockingQueue q) { queue = q; }

public void run() {

try {

while (true) { queue.put(produce()); }

} catch (InterruptedException ex) { ... handle ...}

}

Object produce() { ... }

}

class Consumer implements Runnable {

private final BlockingQueue queue;

Consumer(BlockingQueue q) { queue = q; }

public void run() {

try {

while (true) { consume(queue.take()); }

} catch (InterruptedException ex) { ... handle ...}

}

void consume(Object x) { ... }

}

class Setup {

void main() {

BlockingQueue q = new SomeQueueImplementation();

Producer p = new Producer(q);

Consumer c1 = new Consumer(q);

Consumer c2 = new Consumer(q);

new Thread(p).start();

new Thread(c1).start();

new Thread(c2).start();

}

}}

Given an unbounded non-block queue, implement a blocking bounded queue. Where a Lock replaces the use of synchronized methods and statements, a Condition replaces the use of the Object monitor methods (wait, notify and notifyAll).

public class ArrayBlockingQueue2<E> implements BlockingQueue<E> {

private int count;

private int putIndex;

private int takeIndex;

private Object[] items;

private ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

private Condition notEmpty = lock.newCondition();

private Condition notFull = lock.newCondition();

@Override

public void init(int capacity) throws Exception {

lock.lock();

try {

if (capacity <= 0)

throw new IllegalArgumentException();

if (items != null)

throw new IllegalStateException();

items = new Object[capacity];

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

@Override

public E take() throws Exception {

lock.lockInterruptibly();

try {

while (count == 0)

notEmpty.await();

return dequeue();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

@Override

public void put(E obj) throws Exception {

checkNotNull(obj);

final ReentrantLock lock = this.lock;

lock.lockInterruptibly();

try {

while (count == items.length)

notFull.await();

enqueue(obj);

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

@Override

public void putList(List<E> objs) throws Exception {

checkNotNull(objs);

final ReentrantLock lock = this.lock;

lock.lockInterruptibly();

try {

for (E obj : objs) {

while (count == items.length)

notFull.await();

enqueue(obj);

}

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

private void enqueue(E x) {

items[putIndex] = x;

if (++putIndex == items.length)

putIndex = 0;

count++;

notEmpty.signal();

}

private E dequeue() {

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

E x = (E) items[takeIndex];

items[takeIndex] = null;

if (++takeIndex == items.length)

takeIndex = 0;

count--;

notFull.signal();

return x;

}

private void checkNotNull(Object v) {

if (v == null)

throw new NullPointerException();

}

}

java.util.concurrent.Executor

- An object that executes submitted Runnable tasks. This interface provides a way of decoupling task submission from the mechanics of how each task will be run, including details of thread use, scheduling, etc. An Executor is normally used instead of explicitly creating threads. For example, rather than invoking

new Thread(new(RunnableTask())).start()for each of a set tasks. you might use:

Executor executor = anExecutor;

executor.execute(new RunnableTask1());

executor.execute(new RunnableTask2());

...

- An Executor can run the submitted task immediately in the caller’s thread or spawn a new thread for each task.

class ThreadPerTaskExecutor implements Executor {

public void execute(Runnable r) {

new Thread(r).start();

}

}

- Many Executor implementations impose some sort of limitation on how and when tasks are scheduled. The executor below serializes the submission of tasks to a second executor, illustrating a composite executor.

public class SerialExecutor implements Executor {

final Queue<Runnable> tasks = new ArrayDeque<>();

final Executor executor;

Runnable active;

SerialExecutor(Executor executor) {

this.executor = executor;

}

@Override

public synchronized void execute(final Runnable r) {

tasks.offer(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

try {

r.run();

} finally {

scheduleNext();

}

}

});

if (active == null) {

scheduleNext();

}

}

protected synchronized void scheduleNext() {

if ((active = tasks.poll()) != null) {

executor.execute(active);

}

}

}

java.util.concurrent.ExecutorService

-

An

ExecutorServiceprovides methods to manage termination and methods that can produce aFuturefor tracking progress of one or more asynchronous tasks. It can be shut down, which will cause it to reject new tasks. Upon termination, an executor has no tasks actively executing, no tasks awaiting execution, and no new tasks can be submitted. An unused ExecutorService should be shut down to allow reclamation of its resources. -

Method

submitextends base methodExecutor.execute(Runnable)by creating and returning a Future that can be used to cancel execution and/or wait for completion. Methods invokeAny and invokeAll perform the most commonly useful forms of bulk execution, executing a collection of tasks and then waiting for at least one, or all, to complete. -

Here is a sketch of a network service in which threads in a thread pool service incoming requests.

class NetworkService implements Runnable {

private final ServerSocket serverSocket;

private final ExecutorService pool;

public NetworkService(int port, int poolSize) throws IOException {

serverSocket = new ServerSocket(port);

pool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(poolSize);

}

public void run() { // run the service

try {

for (;;) {

// Listens for a connection to be made to this socket and accepts it.

// The method blocks until a connection is made.

pool.submit(new Handler(serverSocket.accept()));

}

} catch (IOException ex) {

pool.shutdown();

}

}

}

class Handler implements Runnable {

private final Socket socket;

Handler(Socket socket) { this.socket = socket; }

public void run() {

// read and service request on socket

}

}}

java.util.concurrent.ThreadPoolExecutor

-

Thread pools address two different problems: they usually provide improved performance when executing large numbers of asynchronous tasks, due to reduced per-task invocation overhead, and they provide a means of bounding and managing the resources, including threads, consumed when executing a collection of tasks.

-

Programmers are urged to use the more convenient Executors factory methods.

-

New threads are created using a ThreadFactory. by supplying a different ThreadFactory, you can alter the thread’s name, thread group, priority, daemon status etc.

-

Here is a subclass that adds a simple pause/resume feature:

public class PausableThreadPoolExecutor extends ThreadPoolExecutor {

private boolean isPaused;

private ReentrantLock pauseLock = new ReentrantLock();

private Condition unpaused = pauseLock.newCondition();

public PausableThreadPoolExecutor(int corePoolSize, int maximumPoolSize, long keepAliveTime, TimeUnit unit,

BlockingQueue<Runnable> workQueue) {

super(corePoolSize, maximumPoolSize, keepAliveTime, unit, workQueue);

// TODO Auto-generated constructor stub

}

@Override

protected void beforeExecute(Thread t, Runnable r) {

super.beforeExecute(t, r);

pauseLock.lock();

try {

while (isPaused)

unpaused.await();

} catch (InterruptedException ie) {

t.interrupt();

} finally {

pauseLock.unlock();

}

}

public void pause() {

pauseLock.lock();

try {

isPaused = true;

} finally {

pauseLock.unlock();

}

}

public void resume() {

pauseLock.lock();

try {

isPaused = false;

unpaused.signalAll();

} finally {

pauseLock.unlock();

}

}

}

java.util.concurrent.ForkJoinPool

A ForkJoinPool differs from other kinds of ExecutorService mainly by virtue of employing work-stealing: all threads in the pool attempt to find and execute tasks submitted to the pool and/or created by other active tasks (eventually blocking waiting for work if none exist). This enables efficient processing when most tasks spawn other subtasks (as do most ForkJoinTasks), as well as when many small tasks are submitted to the pool from external clients. Especially when setting asyncMode to true in constructors, ForkJoinPools may also be appropriate for use with event-style tasks that are never joined.

You can submit two types of tasks: A task that does not return any result (an “action”, RecursiveAction), and a task which does return a result (an “task”, RecursiveTask).

java.util.concurrent.CompletionService

- A service the decouples the production of new asynchronous tasks from the consumption of the results of completed tasks. Producers submit tasks for execution. Consumers take completed tasks and process their results in the order they complete.

- A CompletionService can for example be used to manage asynchronous I/O, in which tasks that perform reads are submitted in one part of a program or system, and then acted upon in a different part of the program when the reads complete, possibly in a different order than they were requested.

java.util.concurrent.ExecutorCompletionService

-

A

CompletionServicethat uses a supplied Executor to execute tasks. This class arranges that submitted tasks are, upon completion, placed on a queue accessible usingtake. The class is lightweight enough to be suitable for transient use when processing groups of tasks. -

Suppose you would like to use the first non-null result of the set of tasks, ignoring any that encounter exceptions, and cancelling all other tasks when the first one is ready:

public void solve(Executor e, Collection<Callable<Result>> solvers) throws InterruptedException {

CompletionService<Result> ecs = new ExecutorCompletionService<>(e);

int n = solvers.size();

List<Future<Result>> futures = new ArrayList<>(n);

Result result = null;

try {

for (Callable<Result> s : solvers)

futures.add(ecs.submit(s));

for (int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

try {

Result r = ecs.take().get();

if (r != null) {

result = r;

break;

}

} catch (ExecutionException ignore) {

// do nothing!

}

}

} finally {

for (Future<Result> f : futures)

f.cancel(true);

}

if (result != null)

System.out.println("use result!");

}

Why Use CompletionService?

Using a ExecutorCompletionService.poll/take, you are receiving the Future as they finish. Using ExecutorService.invokeAll, you either block until are all completed, or you specify a timeout.

public void demonstrateInvokeAll() {

final ExecutorService pool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(2);

final List<? extends Callable<String>> callables = Arrays.asList(

new SleepingCallable("quick", 500),

new SleepingCallable("slow", 5000));

try {

for (final Future<String> future : pool.invokeAll(callables)) {

System.out.println(future.get());

}

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

pool.shutdown();

}

public void demonstrateCompleteService() {

final ExecutorService pool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(2);

final CompletionService<String> service = new ExecutorCompletionService<>(pool);

service.submit(new SleepingCallable("slow", 5000));

service.submit(new SleepingCallable("quick", 500));

pool.shutdown();

try {

while (!pool.isTerminated()) {

Future<String> future = service.take();

System.out.println(future.get());

}

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

java.util.concurrent.CompletableFuture

CompletableFuture is used for asynchronous programming in Java. Asynchronous programming is a means of writing non-blocking code by running a task on a separate thread than the main application thread and notifying the main thread about its progress, completion or failure.

CompletableFuture implemented the Future and CompletionStage interface. It is a building block and a framework with about 50 different methods for creating, composing, combining, executing asynchronous computation steps with a very comprehensive exception handling support.

CompletableFuture is to a plain Future likes what Stream is to a Collection.

public static void chainFutures() throws Exception {

CompletableFuture<String> completableFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "Hello");

CompletableFuture<String> future = completableFuture.thenApply(s -> s + " World");

assert "Hello World".equals(future.get());

}

public static void combineFutures() throws Exception {

CompletableFuture<String> completableFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "Hello")

.thenCompose(s -> CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> s + " World"));

assert "Hello World".equals(completableFuture.get());

}

public static void combineFutures2() throws Exception {

CompletableFuture<String> completableFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "Hello")

.thenCombine(CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> " World"), (s1, s2) -> s1 + s2);

assert "Hello World".equals(completableFuture.get());

}

public static void runMultipleFutures() throws Exception {

CompletableFuture<String> future1 = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "Hello");

CompletableFuture<String> future2 = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "Beautiful");

CompletableFuture<String> future3 = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> "World");

String combined = Stream.of(future1, future2, future3).map(CompletableFuture::join)

.collect(Collectors.joining(" "));

assert "Hello Beautiful World".equals(combined);

}

public static void handlingErrors() throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException {

String name = null;

CompletableFuture<String> completableFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> {

if (name == null) {

throw new RuntimeException("Computation Error!");

}

return "Hello, " + name;

}).handle((s, t) -> s != null ? s : "Hello, Stranger!");

// An alternative way to throw an exception!

completableFuture.completeExceptionally(new RuntimeException("Calculation failed!"));

assert "Hello, Stranger!".equals(completableFuture.get());

}

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

chainFutures();

combineFutures();

combineFutures2();

runMultipleFutures();

handlingErrors();

}